Who Are We?

Théâtre de la Ville performs Luigi Pirandello’s Six Characters in Search of an Author at the Power Center in Ann Arbor on Oct 24-25, 2014. Photo by JL Fernandez.

While I was working on a biography of poet, playwright, and theatre director Federico García Lorca many years ago, I was startled to discover that Lorca had planned to meet up with the dramatist Luigi Pirandello in Italy in 1935. The two intended to collaborate—but Lorca cancelled the trip after Mussolini invaded Abyssinia (it was one of the rare overtly political gestures of Lorca’s life), and the two men never met.

I’ve often wondered what would have happened if they had. For both playwrights shared, among other things, a fascination with the nature of theater. Lorca probed the topic throughout his life, in plays that contain plays and rehearsals within plays, plays whose cast lists include directors and actors and playwrights (including Lorca himself). He introduced all manner of theatrical claptrap into these works—puppets, masks, screens (behind which identities abruptly change), miniature stages, outlandish costumes and props.

Pirandello was similarly obsessed. You see it big time in Six Characters in Search of an Author, a play that, if done well, should produce something like imaginative whiplash in the audience. (I’ve only seen the work produced once, in a student production at NYU, with way too much scenery-chewing. But having seen Théâtre de la Ville’s exquisitely nuanced production of Ionesco’s Rhinoceros two years ago in Ann Arbor, my hopes are high.)

What’s real? Who’s acting?

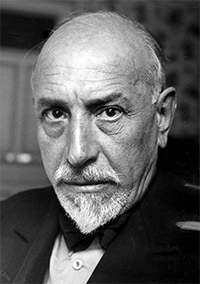

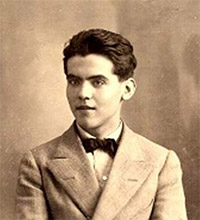

On left, Luigi Pirandello, and on right, Federico García Lorca.

What’s real? Who’s acting? Are the events and emotions we see onstage reality? Is what we experience and witness in “real life” acting? Can you trust what you see on a stage? In a conversation with your spouse or best friend or boss?

Aren’t these the questions that lie beneath the pleasures we associate with theater? (With film too, but I don’t think the experience is ever quite as acute on a screen.)

The setup for Pirandello’s exploration of theatrical artifice is straightforward: six purportedly fictional characters barge into a mostly empty theater to impose their story on a director and group of actors who are trying to rehearse a play. Actors become audience. Characters become actors. The layers multiply and confusions mount.

In line after line, we’re asked to consider the contradictions at the heart of play-making.

DIRECTOR: Then the theater is full of madmen, is that what you’re saying?

FATHER: Making what isn’t true seem true … for fun … Isn’t that your purpose, bringing imaginary characters to life?

Elsewhere the Father—one of Pirandello’s “six characters”—cries out that his story isn’t literature, it’s “life! Passion!” To which the Director responds: “That may be, but it won’t play.”

“What’s a stage?” a character asks toward the end of the play, and answers her own question. “It’s a place where people pretend to be very serious.”

The Empty Space

Exchanges like this abound—and make you question the theatrical enterprise and its conventions. Do we really need all the devices we’ve come to associate with the theater? The curtain and spotlights and scripts and applause? Peter Brook famously said (in his indispensable 1968 book The Empty Space) that in order for an act of theater to take place, all you need is for one person to walk across an empty space while another watches.

Brook published his book some 40 years after Pirandello wrote Six Characters, which opens on a stage whose atmosphere, Pirandello instructs, “is that of an empty theater in which no play is being performed.”

The Italian Pirandello grew up steeped in the venerable stuff of theater—the comic and tragic masks of the ancient Greek and Roman stage, the stock characters of thecommedia dell’arte. He understood (as did Lorca and that greatest of playwrights, Shakespeare) that identity is at the core of acting. As one of Pirandello’s six “characters” points out, “We all try to appear at our best, but we all know the unconfessable things that lie within the secrecy of our own hearts. We are not what we seem—even to ourselves.”

Don’t you change your personality according to the situation and your audience?

In another book I find indispensable, The Actor’s Freedom: Toward a Theory of Drama (1975), critic Michael Goldman probes precisely these questions. Identification is the “covert theme of drama,” Goldman writes. This isn’t simply a matter of actors identifying with roles but of “the making or doing of identity.” You watch an actor, onstage or on screen, and wonder where her private life stops and the public, performed one begins, what parts of herself we see revealed in her role.

“It should not be surprising, then,” says Goldman, “that the process of identification in this sense—of establishing a self that in some way transcends the normal confusions of self—is remarkably current as a theme in plays of all types from all periods, from Oedipus to Earnest to Cloud Nine.” Add Six Characters to that list.

And what about us? Are we characters—locked into our one and only story? Or actors, whose “solid reality as of this moment is destined to become the half-remembered dream of tomorrow,” as Pirandello’s Father puts it?

Questions to ponder, indeed. Endlessly.

Leslie Stainton’s most recent book is Staging Ground: An American Theater and Its Ghosts, a poignant and personal history of one of America’s oldest theaters, the Fulton Theatre in Lancaster, Pennsylvania.